Social-Emotional Learning: New education methods in a changing system

David Winkle has worked for more than 23 years as a school counselor in Arizona. He began his career in Patagonia, a small high-desert town that rests 19 miles from the border town of Nogales.

In Patagonia, Winkle worked closely with students who were suffering academically and emotionally. He offered guidance to many who wished for a future away from the opportunity barren town, while also serving the emotional needs of students by creating counseling groups for kids who were dealing with grief, loss, or low self-esteem.

Winkle was the entire counseling department in Patagonia from kindergarten through high school and worked with limited resources. It was daunting, but he was pursuing work that he believed would make a difference.

After spending his pre-masters work as an agency counselor for Arizona Children’s Association, Winkle shifted his career focus because he believed his clients and others were not seeing positive gains. Working in schools seemed more hopeful in his eyes. He believed he could have a greater impact inside the school rather than out.

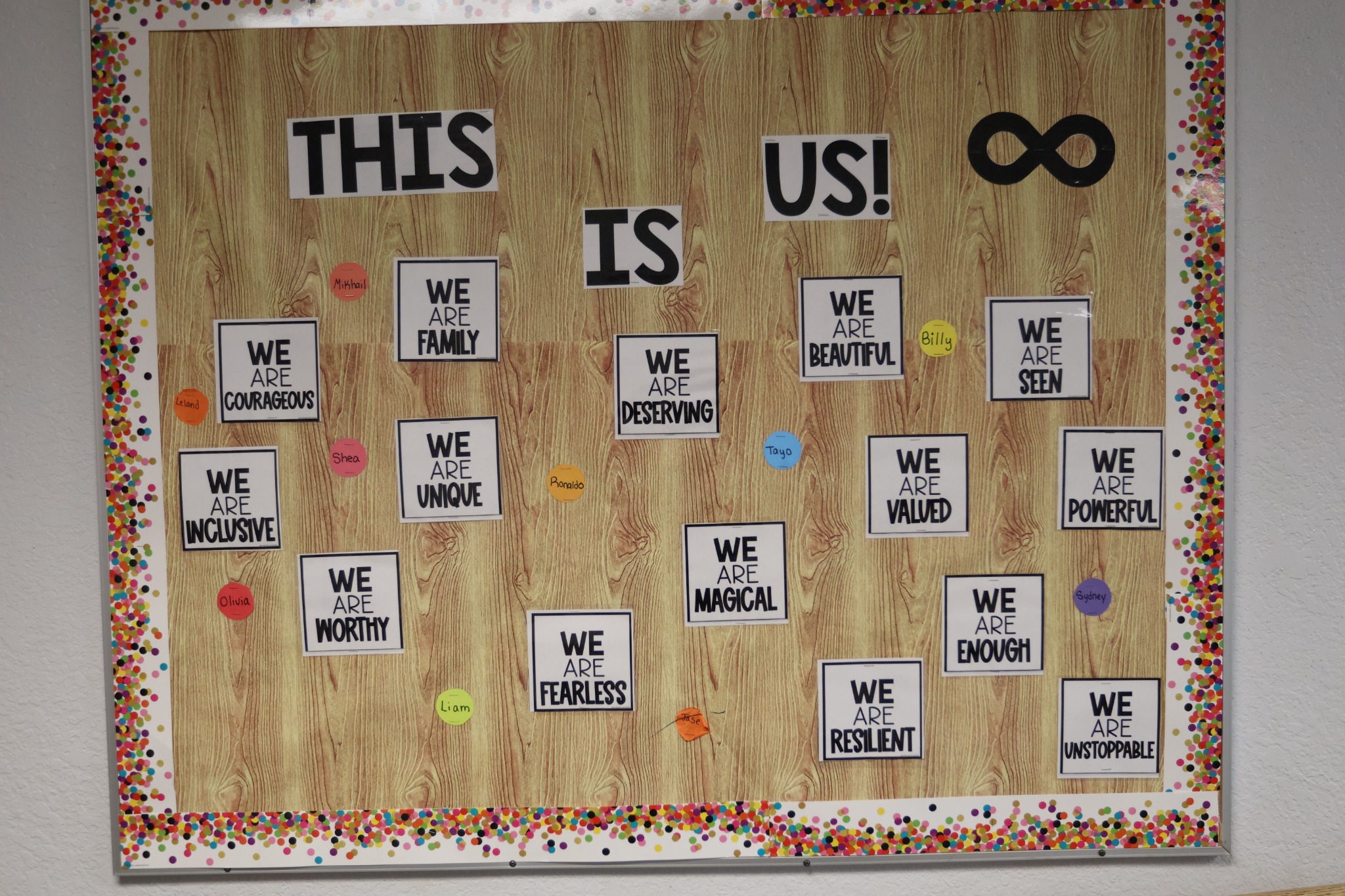

While in Patagonia, Winkle incorporated social-emotional learning (SEL) lessons into his work because he saw it as a need in the district. SEL is meant to help students develop skills to support healthy relationships, show empathy and make responsible decisions. Students were struggling and needed support in their quest for a better future.

When Winkle departed Patagonia, he was surprised to learn that not every counseling position is alike. He had been in multiple schools, including Buena High School in Sierra Vista, where his job consisted of academic advising and therapeutic-type work for students who were struggling behaviorally.

It was in positions at Chaparral High School and in his current job as advisor at Ben Franklin Charter School in Queen Creek that Winkle learned about the varying dynamics of counseling in Arizona.

At Ben Franklin, Winkle is purposely identified as an advisor. Solution-based counseling and implementation of SEL curriculums are used as-needed because the school’s main priority is on academic success. This became evident in Winkle’s interview for the position, as he was told that his predecessor was doing too much SEL and the administration wanted someone who was more college and career focused.

Winkle was prepared to offer the best service to any and all students who sought college and career preparation, but he was quick to dispute the idea that has come up in many of his workplaces — that SEL in counseling is akin to therapy.

“There’s a misperception that brief, solution-focused based counseling at a school is therapy,” Winkle said. “It’s therapeutic, but it’s not therapy in the sense that I think that it’s perceived by the people who started and operate the school.”

Less SEL, more advising, is an idea that seems to be shared by many academic-focused schools in Arizona that Winkle has worked with. However, it is also a sentiment that is passed down by the state Department of Education and Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction, Tom Horne.

When Horne retook the Superintendent’s office in January 2023 he said his №1 priority was to return the Arizona Department of Education to a focus on academics and to increase test scores. Arizona, like many states, showed no improvement in reading scores and had significant declines in math scores on the 2022 National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP), which is given biennially to a sample of fourth- and eighth-graders in every state.

Some decline on the NAEP could be attributed to an extended absence of in-person instruction due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Scores indicated that only 26% of eighth-graders nationally were proficient in math, while the average math score fell in every state except Utah. However, Arizona’s declines were part of a continuing drop in average math and reading scores since 2013.

As a part of Horne’s reintroduction to education, he revealed a new mission statement for his department: “The Department of Education is a service organization dedicated to raising academic results and empowering parents.”

Included in Horne’s vision for Arizona was a stance on discipline and SEL specifically that many educators across the state have taken exception to. In his inauguration ceremony he promised a “return to traditional discipline,” which he later clarified as suspensions and expulsions. Horne also attacked SEL, calling it “a front for critical race theory,” in an interview with the Arizona Mirror.

“The public is becoming increasingly aware that debunked CRT programs should not be in the classroom, so school personnel wishing to include it in their curriculum find ways to sneak it in,” Horne’s office said in a statement when asked to clarify how SEL promotes critical race theory. “SEL often serves that purpose, a Trojan horse, within which instructors can usher in an array of questionable lessons without transparency and under the guise of a less polarizing term.”

Horne called to replace SEL curriculum with a program called Character Counts, which was used previously in schools during his tenure as state superintendent from 2003–2011. Character Counts focuses on the values, attitudes, mindsets, and skills of students through the understanding of the six pillars of character: trustworthiness, respect, responsibility, fairness, caring and citizenship.

In some smaller public schools, Character Counts was incorporated into everyday activities by calling students over the intercom to the office where they would receive a bracelet for the corresponding character trait that they displayed to earn the honor.

“The Six Pillars program is about developing character, where students learn to take personal responsibility for things like their happiness, success, behavior, choices, and the productive ways they would like to serve their communities, their state and country,” Horne’s office said. “SEL programs often teach the opposite, making students feel like they are victims of circumstances beyond their control or that they cannot succeed in life without government assistance and intervention.”

To encourage schools to adopt Character Counts, the Department of Education announced in February 2023 that any school that teaches a character education curriculum is eligible to receive a Character Education Matching Grant.

Eligibility requirements under state law show that it is necessary for school districts to define and apply at least six of the following traits during explicit instruction: truthfulness, responsibility, compassion, diligence, sincerity, trustworthiness, respect, attentiveness, obedience, orderliness, forgiveness, virtue, fairness, caring, citizenship and integrity. Fifteen of Arizona’s 261 school districts received grants from the first year of applications.

“The focus should be on academics because students today are subjected to far too many distractions,” Horne’s office said in a statement. “These can include things like (critical race theory) and SEL, but also misbehaving students that disrupt the class and make it very difficult for teachers to maintain an effective learning environment. (Horne) believes school boards must direct administrators to support teachers by restoring discipline to the classrooms, up to suspension and expulsion of unruly students, when necessary.”

Horne himself went into detail shortly after his inauguration about the distractions to education in Arizona.

“My goal is to have the kids learn more and get the test scores up. They’re in the bottom of the well right now. It’s a tragedy. It’s an emergency,” Horne said in an interview with Fabiola Cineas for Vox.

Many educators agree with Horne’s statement that Arizona is in a state of emergency in regard to education, but the feelings of those in districts small and large whose profession it is to help students mentally and behaviorally, push against the idea that test scores should be the main priority. Those on the front lines, such as Knoles Elementary School kindergarten teacher Danielle Donaldson, believe that standardized testing is a cause for stress in the minds of students and teachers alike.

“It’s not appropriate for the students most of the time,” Donaldson said. “It also kind of makes the teachers feel cruddy. It makes them feel like their worth is dependent on how their students’ scores are. When I don’t think that standardized tests really show what students know. It makes everyone feel bad.”

Donaldson and others in her home district of Flagstaff share a strongly held belief that the whole child must be taken care of for them to reach their academic potential. In many cases it begins with implementing an SEL curriculum that is fitting of a district and community. However, limited resources for SEL and public schools in general hinder progress from the beginning.

“It seems that the legislators in Arizona do not like public education and have, in my opinion, deliberately and systematically tried to reduce its already pathetic funding to the point where the public schools, no matter how good the teachers might be, are going to struggle. Which opens the door for what we have now,” Winkle said in response to Arizona’s recent expenditures on education.

“Public schools are in real trouble in Arizona and it’s not getting better,” he said.

What is Social-Emotional Learning?

Recent criticisms of SEL may cause some to think that it is a newfound phenomenon, but the reality is that it has been in the educational lexicon since the early 1990s due to efforts by an organization known as the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL).

In 1994, a group of educators and researchers collaborated to found CASEL and create a multidisciplinary field that would address what the CASEL website refers to as the “missing piece” in education. The effort was led by Timothy Shriver — a member of the Kennedy family, former teacher, and Special Olympics chairman since 1996 — and Dr. Roger Weissberg, a psychology researcher from the University of Rochester and the original chief knowledge officer and board vice chair for CASEL.

The group’s work came after the success of the Comer School Development Program, a program that was set forth by James Comer, a professor of Child Psychiatry at the Yale Child Study Center. The program involved and still includes parent education, collaborations with local early learning organizations and network development through the city to inform policy making decisions at all levels of government.

The next advancement in SEL came in 1997 when Weissberg co-authored the book Promoting Social and Emotional Learning: Guidelines for Educators with nine other SEL collaborators. The book formally defined SEL, giving educators who were trying to develop social and emotional competence in children a basis for their work.

Over time, SEL curriculums grew in popularity. A 2017 systematic review of SEL standards across all 50 states by professors at the University of Missouri and University of Wisconsin-Madison found that every state has clearly defined freestanding SEL standards for preschool education, but only 11 states have SEL standards at the K-12 level. The review also showed that 20 states include CASEL standards for SEL in counseling practices. Arizona was not one of them.

Despite the lack of buy-in from every state, the results from explicit SEL instruction have been evident. Counselors like Winkle know this as truth because he has heard from former students who have told him about the difference he made in their lives.

“It did help those kids,” Winkle said. “I have those kids tell me 10, 15 years later that ‘the group you did when our classmate died, that really helped me.’ So I know that it did have a really positive impact.”

Winkle’s experience is not an outlier. A 2011 meta-analysis that was co-authored by Weissberg showed that students who participated in programs that covered the five core competencies laid out by CASEL — self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills and responsible decision making — had an 11% gain in achievement compared to students who did not participate in SEL.

A 2022 study analyzing project-based mathematics (PBM) lessons in elementary schools also found that incorporating SEL skills into science and math exercises engaged students and enhanced learning purpose in elementary classrooms, which was supported by the evidence of students’ full participation and functional final products.

Lessons included making a “grabber” for an Easter-themed project that allowed students to consider others when deciding on the length and effectiveness of the tool. While another project prompted students to recycle items from their living surroundings and turn it into something practical for their peers.

Three students ended up creating a mini air hockey table from cardboard and bottle caps, which was praised by other students who said it was successful because of the team’s responsible decision making and community benefit.

SEL has economic benefits as well.

A 2015 cost-benefit analysis done by Cambridge University of an SEL program known as Second Step, which is used in various schools throughout Flagstaff, reported a net benefit of $276,000 per 100 students by being able to increase social competence and reduce aggressive behavior in children. On a national scale, over $1.7 billion was spent on SEL materials during the 2021–2022 school year according to a report. That marked a 22.9% increase in spending from the 2020–2021 school year.

For Emily Saunders, a licensed clinical worker and somatic educator in Arizona, the positive effect of SEL can also expand beyond the benefit to students. In her view there is beauty in being able to bring SEL to students and teachers, allowing educators to tend to their own emotional lives while building deeper relationships with the people they are often spending 40–50 hours a week with.

“It enriches our whole culture,” Saunders said. “It’s good for everybody. We can be given permission to be more human in an ideal setting. It can be really exciting to start to learn about how your nervous system works or to understand intergenerational trauma because a lot of times we’re carrying a sense of defectiveness and shame that with this kind of education, we get to externalize.”

Saunders finds hope in her work, feeling that adults like her who instigate change and have an inner magnet toward harmony may help SEL grow.

The larger impact of Social-Emotional Learning

Arizona educators are often tasked with extreme workloads. According to the American School Counselor Association, the ratio of students to counselors in Arizona for the 2022–2023 school year was 667-to-1, the highest in the nation and more than double the recommended ratio of 250-to-1.

In the classroom, the ratio of students to teachers in 2021–2022 was 22-to-1 according to the National Center for Education Statistics. The recommended ratio is 16-to-1.

On top of these issues, limited funding now forces schools like Knoles Elementary to cut positions. In Knoles’ case, it means losing a kindergarten teacher and forcing the remaining staff to take on higher class sizes.

Donaldson has had six years of experience teaching kindergarten and is prepared for what is to come, but teaching academics on top of trying to manage more than 20 little souls can bring on an almost post-workday catatonic state in which there is nothing more to do than sit on the couch and decompress.

“Having a large class size is really difficult because of their big emotions,” Donaldson said. “Managing it as one human being and also going home and not being compassion-fatigued after hearing all the situations and all the emotions, sometimes it’s really hard. When you have 28 big emotions all day, that’s a lot on one person.”

Donaldson has been able to handle situations like these in part because of the lessons she has learned from the Knoles school counselor Gary Hubbell.

When in-person instruction returned post-pandemic, Hubbell focused on self-care and the internalization of emotions. Donaldson realized through Hubbell’s lessons that internalized emotions can affect younger students as much as it does older ones. She leaned on Hubbell in difficult situations and was able to understand the feelings her students were experiencing, while also incorporating strategies that allowed her to calm down raucous classes and steady herself in the process.

Understanding her students let Donaldson feel increasingly comfortable in a position that she always wanted to be in, giving her a lane to make an impact in the way she envisioned in her youth.

“I knew I didn’t want to do anything else,” Donaldson said. “I didn’t have the best experiences as a child in school and I realized about myself that I could provide that positive experience for students.”

Donaldson and many of her peers at Knoles were receptive to the ideas Hubbell integrated, but mindfulness and emotional regulation are not always strategies that prevail.

Curiosity and guidance are approaches that require time and resources, both things that the Arizona legislature is not always willing to provide. In the classroom, a lack of resources and push to teach academics can leave educators vulnerable to unawareness according to Saunders, who has worked with individual students and districts across Arizona and New York.

It is heartbreaking, in Saunders’ eyes, to see the rich emotional lives of students become overlooked by those who are meant to support them through their youth. In schools where emotional support is not a priority, Saunders often sees strategies that are effective for teachers, but not beneficial for the student.

“When students’ emotional lives do surface in a way that’s disruptive, the strategy is power and control over, as opposed to meeting that young human and understanding and being curious,” Saunders said. “Those strategies let the adults stay emotionally regulated and it puts the burden on the kid to have to deal with their suffering.”

These situations are not ideal, but Saunders says that human emotion can often elicit responses that are representative of the general dominant culture in Arizona and beyond.

“Anytime we’re with anyone who’s having a rough emotional time, it’s eliciting our own emotions,” Saunders said. “I think for a lot of adults who haven’t had the support or who haven’t been given permission to feel those feelings, that being around that kind of vulnerability in young people, it’s just really scary.”

The system itself may also be a reason why change is not quick to come.

Saunders and Julie Lillie, a Peace Educator in Arizona, focus on the idea that American schools were formulated to create a work force. It is an inherent tension according to Saunders and does not pair well with the introduction of SEL or trauma-informed practices.

“We need to shift out of that and have a wider whole person, holistic focus which prioritizes the individual person, relationships and a sense of belonging,” Lillie said.

Lillie also stressed the importance of academics, but recognized that emotional regulation is an overlooked piece of education that, if taken seriously, can have a major impact on how education systems operate.

“Being able to navigate your emotions and communicate with nonviolence and solve problems and have a sense of inner peace,” Lillie said. “That is of equal importance, if not even more important as a foundation of which then academic learning can be built upon.”

However, there is resistance inside of schools in the way of educators being resistant to new ideologies. Saunders mentions that defensiveness and protectiveness are substantiated reactions for someone being told that the way they manage a classroom is not ideal.

The question then arises for those implementing SEL strategies, what are the conditions that allow for change?

It begins with delivery.

Saunders says people need a sense of agency that allows them to get in touch with their inner selves without being pressured from outside sources. Being sincere with teachers can help educators like Saunders, Lillie, Winkle or Hubbell offer support in the right ways. As with teachers like Donaldson who feel that the state does not value them or their students, being genuine and providing validation to teachers’ concerns is the simplest way in Saunders’ view to begin changing classroom management methods and student behavior support.

In this hands-on approach where communication between educators leads to improved student performance, there is still a wall that separates those in Arizona from receiving the same support as their counterparts around the country: funding.

A 2023 report from the Education Law Center that examined school financing over the 2020–2021 school year found that Arizona ranked 49th in per-pupil funding, spending $10,670 for every student. That was still $5,461 below the national average of $16,131. Only Idaho placed lower with per-pupil funding of $10,526.

More recent data showing inflation adjusted numbers from the Arizona Joint Legislative Budget Committee says that the state spent $12,003 per student in 2023, but that total dipped to $11,376 in 2024.

A lack of resources

Per-pupil funding tells only part of the story in regard to Arizona’s education budget. The report from the Education Law Center also measures a state’s distribution of funds between low- and high-poverty districts, as well as its ability to raise education funding when compared to the gross domestic product.

Arizona scored a C and F grade respectively in the two areas, showing that funding is not targeted to low-income schools and that the state’s effort to fund schools is below average.

The effects are felt in schools across Arizona.

At Knoles Elementary 53.6% of enrollees are minority students, while 19% are economically disadvantaged. These are not uncommon numbers for a school positioned in one of Flagstaff’s wealthier neighborhoods, but the need for funding is still felt as teachers are set to be cut and in-school resources for behaviorally challenged students continue to dwindle.

The impact of Arizona’s lack of education spending shows up even more so in smaller districts where a large majority of students are both minorities and economically disadvantaged.

Ajo Unified School District and Gila Bend Unified School District, each sitting within 81 miles of the Mexico-United States border in southwest Arizona, are home to a student population that is 90% minority students and at least 51% that are economically disadvantaged.

Each district has one pre-K-12 school that has far less than 1,000 students in attendance at any time. This means less overall funding from the state and a lack of support services that are often not adequate to handle student behavior issues.

Suspension, and expulsion when necessary, an idea that was reiterated during correspondence with Superintendent Horne’s office, then becomes the preferred method when handling extreme cases of misbehavior.

Quick reactions and a lack of communication between school administration and community can actively turn a small community against its only school. Saunders has seen it herself through work in Ajo.

“It’s really effective when schools try to be transparent and communicative about what they’re doing,” Saunders said. “I really saw this up close in Ajo. When the administration was communicative and transparent about mistakes they made or about hard things that happened, the community was able to be on board and collaborate with them. But when the school kind of battens down the hatches, then the community of course felt skeptical.”

Pressure in a small community can have an impact on the care and well-being of students in the classroom. Community members become upset with how the school operates, while conversely school administration is forced to handle more pressures on top of already limited resources from the state government.

In these districts, there is usually more need than there are resources according to Saunders. In association, educators and special education teams can become so disconnected that they unconsciously disregard students’ mental health.

“Prioritizing relationships with parents and community leaders and resources is just absolutely huge, but it’s a hard thing to ask teachers and especially administrators to do because they’re already overburdened with what they’re being asked to do,” Saunders said. “I’ve seen this so many times working with individuals, I don’t even think it’s conscious; they look the other way because they’re saturated, they don’t have the resources to meet the needs.”

As a result, students appear to have less care about what the future has in store for them.

Former Ajo counselor and principal Dan Morales saw such decline in his 27 years as an educator in the small desert town. Ajo used to be heavily supported by an open-pit copper mine that brought in revenue and workers. When the mine closed in 1983, it caused an influx of people to leave town, changing the atmosphere and attitude of locals.

“You didn’t have the parents that were instilling in their kids, to go to college, to go further,” Morales said. “And if they did, they didn’t know how.”

Now as the administrative chief at Ajo Ambulance, Morales sees some of the same attitude toward school as he did during his tenure.

“You have a generation of kids coming up that are not prepared emotionally or socially to seek anything beyond ‘what is the police department going to give me’ or ‘I’m going to Phoenix to get a job,’” Morales said. “The kids started to change. The atmosphere in the school started to change.”

Winkle, who spent the 2021–2022 school year in Gila Bend, saw similar ideals prevail in his time in the district. When entering Gila Bend, Winkle assumed that expectations for students and staff would be the same as other schools he had worked with. That was not the case.

The tenured school counselor, who spent more than two decades in Arizona schools, was surprised to learn that there was not much structure to his position. Winkle thought Gila Bend would be similar to Patagonia, another small school with a large population of minority and economically challenged students. In those ways Gila Bend and Ajo are akin, but Winkle felt like an outsider from day one in his time in the rural town.

Winkle described that students and staff in Patagonia were curious, which led to surprise when he could not find any Gila Bend students who were interested in finding higher education.

“I just had a hard time relating to them because they weren’t what I thought,” Winkle said. “The Patagonia kids, even though they didn’t know a lot about college, they were interested and they wanted to get out. They would proactively seek me out to try to help them get out of their situation, to better themselves, to go onto something bigger and better. I had a hard time finding the Gila Bend students that wanted that.”

Winkle does not place blame on the students, but rather critiques the administration that was unable to formulate a plan for its counselor.

The Gila Bend superintendent at the time seemed unsure of how to help the students during Winkle’s tenure. Winkle attempted practices that had worked in previous environments, but all attempts fell short as he could not connect with students.

“I think he was just hoping that I could come in and just know what to do,” Winkle said about the Gila Bend superintendent. “Whenever I asked him a question about ‘what do you think about this,’ he would never give me a real answer. So I took that as he doesn’t really know what he wants and he just hopes that I can figure out what to do. But I couldn’t figure out what to do out there. The things I tried were things that worked in other places, and it didn’t work.”

During the 2021–2022 school year Gila Bend spent $1,607 on student support services, almost double the amount of the previous school year. However, after Winkle left and new administration members were brought aboard, funding suddenly dropped. In 2022–2023, student support services received $1,069 with less dollars going toward health, attendance and social work services than in years prior.

Winkle’s departure also left the district without a certified counselor. The school now employs a counselor who has a background in suicide prevention and youth mental health, but their certifications are not equal to many other educators in similar roles.

Implementation

Not all school districts are in a position to rely on a single counselor’s work as the only option to improve student achievement.

Flagstaff Unified School District, home to 16 schools, is working toward providing centralized learning objectives across all its schools so that every student is receiving the same type of education.

All sectors are seeing staff from around Flagstaff come together for planned “Collaboration Days,” where issues are discussed anecdotally and addressed as a collaborative effort.

This year, Flagstaff Unified District began bringing together counselors as a part of the collaboration to address student behavior issues. John Shirk, the Director of Student Support Services for the district, says that zones of regulation and improved student behavior has been the main discussion during meeting times.

Many school districts operate in a similar fashion, but Shirk feels that Flagstaff prioritizes student behavior and mental health more than previous districts he has worked in, such as Tempe Union.

“I feel like Flagstaff has got a higher priority than the other districts that I’ve worked in,” Shirk said. “Not that they’ve been bad at the other districts, but it’s a huge focus here. I mean this department doesn’t exist in a lot of places. Everybody does suicide prevention and some kind of mental health stuff and everybody does obviously discipline and behavior, but the approach here and the focus on being cognizant of trauma and restorative practices and having a district-wide implementation of restorative practices. I don’t think that is always the case.”

Economically, Flagstaff Unified spent more on support services during the 2022–2023 school year, $2,356, then Tempe Union, which spent $2,250. Flagstaff also out-spent the largest district in Arizona, Mesa Unified, by a small margin.

Shirk highlights that while his department is only responsible for student support and behavior, it is part of a larger goal to give students the best educational experience possible.

When students returned from Covid-19 school closures, there were many who struggled to fit into the grade they were supposed to be in. Shirk said there were three years’ worth of first-year high school students who did not know how to be high school students.

SEL then became an important tool to teach those students how to cope and behave in a new setting so they could be academically successful at the high school level.

“There’s a lot of different areas that all kind of intersect,” Shirk said. “I think being able to take care of students on a variety of different levels, academics and otherwise, is really important in being able to explicitly teach students. I think that’s what you’re getting at when you talk about SEL, is teaching our kids how to do things in appropriate ways given the struggles or needs that they individually have and helping them do better, learn how to be better, be better students, be better people, build better character. It’s easy as a default to kind of just have expectations and hold people accountable for things.”

With district-wide implementation of SEL practices comes an understanding of intention.

Saunders mentions that the unstated intention of practices that address student behavior can be to control students. It is not malicious in nature, but at times SEL may be used by educators to calm down students so that instruction is possible. Where SEL differs from traditional student discipline is that it allows students and their families to change their behavior.

“Asking kids to sit still is not the same as really getting in there with them and helping them reflect on what their needs are in the moment,” Saunders said.

Saunders continued to say that SEL practices do not always need to have a hyperfocus on what happened to a student. It can be beneficial to those supporting the student so they can show true compassion, but Saunders observes that helping kids find their own medicine within can be the best thing for them.

Although there is confidence in educators and Arizona’s citizens to support future generations, Saunders knows the current situation is less than ideal.

“I think the systems right now are not supporting our kids and we gotta be really honest about that, but there’s a lot we can do,” she said.

Post a comment